Alex web

A Marriage of

Lives and Photos

The photographers Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb have produced a book, “Slant Rhymes,” that pairs images by each of them in diptychs. In an email exchange with James Estrin, they discussed the book, photography and their relationship.

What is this book about, and why the title “Slant Rhymes”?

Alex Webb: This book — which pairs one of my photographs with one of Rebecca’s — is a kind of visual conversation between us. It reflects our nearly 30-year relationship, from our initial rich friendship to our marriage to our decision — some 20 years after meeting one another — to collaborate on our first photography book, “Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs From Cuba,” and to continue collaborating over the next decade. Some 10 years ago, when we first spread our small Cuba prints on the floor of our hotel room in Cadiz, Spain, we began to see that our photographs talk to one another in surprising ways.

Rebecca Norris Webb: And sometimes our photographs even “rhyme,” something Pico Iyer wrote about in the afterword to “Violet Isle,” a notion I’ve found myself returning to while working on our next two collaborations, “Memory City” and “Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image.” Since we have two linked but distinct styles, however, our photographs seem to rhyme at a slant, more akin to what’s called a slant rhyme in poetry, a pair of words that don’t rhyme exactly, such as “blue” and “moon.”

How do your photographs speak to each other?

A.W.: The photographs in this book tend to be suggestive and ambiguous rather than rationalistic. It’s often difficult to put into words just how they relate, or speak, to one another. Sometimes it’s a shared palette or geometry that links our photographs, other times a shared geography or subject or tone. In addition, we both embrace a kind of surrealism, although seemingly in two different keys: Rebecca’s more in the spirit of Bach’s D Minor Partita that she so loves, mine more in the spirit of the blues, as in Albert King’s “Born Under a Bad Sign.”

R.N.W.: And sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint exactly how our photographs speak to one another. The closest I can come to begin to explain this mystery is that it’s related to the way the most surprising metaphors work in poetry — the more distance between the two things being compared, the greater the leap of imagination needed to bridge the gap.

How is the relationship between your images similar or different from your relationship?

A.W.: As I can’t fully explain how our images relate to one another, it’s equally difficult to try to explain the nature of our relationship. Perhaps making “Slant Rhymes” is our way of attempting to express something about the relationship between our ways of seeing and being.

R.N.W.: And I’d add that the relationship between us — as well as between our images — are both sustained in part by a deep faith in mystery itself, that elusive creature we hope some of our strongest work corrals, at least for a moment.

“We both embrace a kind of surrealism, although seemingly in two different keys: Rebecca’s more in the spirit of Bach’s D Minor Partita that she so loves, mine more in the spirit of the blues, as in Albert King’s ‘Born Under a Bad Sign.’”

Some of the photos in the book are out of the context they were taken. How do they function in this book?

A.W.: While some photographs in this book initially appeared in a different context, they can live just as successfully in another, because they are complex images with multiple potential meanings. After all, is this so different than photographs of mine from “La Calle” — which are specifically orientated towards the world of Mexico — also appearing in “The Suffering of Light,” where they’re seen in the context of a photographer’s way of seeing in color?

In the introduction to “Slant Rhymes,” I touch on this notion when discussing Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. When I took this photograph in 1996 — an image that differs in tone from my hard-edged work from the border — I didn’t consider that Rebecca and I had just come together as a couple. It was only later that I began to understand the significance of this photograph. Although it’s inhabited by those deep shadows dominating much of my border work, this particular photograph is quieter, more lyrical. It’s as if its human moments — the couple embracing, the father holding his daughter — somehow manage to keep the darkness at bay, at least briefly.

R.N.W.: It’s intriguing how certain documentary photographs slowly begin to have a life of their own, making their way in the world untethered from time and the original publication where we first remember seeing them. I also like how “Slant Rhymes” incorporates new work — about a third of the images have never been published.

Photography is usually a fairly solitary pursuit. Is the process of photographing different when you do a book together, like “Violet Isle”? Is the process of making a book different when it is only one of you, as opposed to both?

A.W.: The process of working together has varied somewhat with each collaborative project. “Violet Isle” was our first joint book, and it wasn’t until our 11th and final trip to Cuba that we decided to bring our two separate projects together as a joint book, so the collaboration evolved rather organically. With “Memory City,” however, which we conceived as a joint project from the start, we had to learn to navigate our very different creative rhythms. Whereas I tend to dive into a project, Rebecca often wades into it, slowly finding her way to the metaphors that guide her work.

And although the actual act of photographing for a collaborative project is pretty similar to that of an individual project — since we rarely photograph together — the editing process is quite different and more challenging.

R.N.W.: When editing and sequencing one of our monographs, we encourage each other to be tough on the work, but we have one essential—and perhaps marriage-saving—house rule: The author has the final say. That’s why our collaborations are trickier. Thankfully, we’ve found if we leave our small prints taped to our studio wall in the sequence we’re considering for a few weeks or months, our disagreements eventually get worked out. So I guess you could say that time has become our silent collaborator. Time, we find, is the best editor.

Both individually and together you have made a lot of books. Why do you do this so much? Can you describe why books are so often the main output of your work?

You teach bookmaking workshops together. Why do you love making books?

A.W.: Photography seems uniquely suited to books. A book can never capture the texture of a painting or the three dimensions of a sculpture, but it does a pretty good job of giving a sense of a photograph. Furthermore — and this may reflect Rebecca’s and my background in literature—we’re both intrigued by the sequencing of photographic books, especially how the relationships between photographs can expand one’s understanding of a project. I love exhibitions, but ultimately they are more temporal. Books endure.

R.N.W.: I love the paradox of being able to hold in one’s hands a series of intangible moments.

And no matter how many books one makes, each one is a unique creative challenge. With “Slant Rhymes,” I especially like how the design echoes a poetry book, with its cloth cover and tipped-in image on the front of the book.

“When editing and sequencing one of our monographs, we encourage each other to be tough on the work, but we have one essential — and perhaps marriage-saving — house rule: The author has the final say.”

I’m curious, why do each of you individually photograph?

A.W.: What else would I do with myself?

I love exploring the world with the camera — wandering and occasionally finding something that is more startling and revealing than that which I could ever imagine. It’s why I’m a photographer and not, say, a painter. And there are those rare times — when the light seems right, and I seem attuned to the world and able to move seamlessly in and out of various situations — when I feel that photographing in the streets is what I was put on the earth to do. And then, of course, there are those other moments — all too common — when the photographs aren’t working, when I’m frustrated and unhappy, when I wonder why I keep trying to do something so difficult and elusive …

R.N.W.: Photographing is my way of trying to understand love and death, memory and landscape, in this confounding world of ours that’s filled with beauty and suffering. I work deeply and intuitively, often walking or driving in a landscape where I’ve lived or spent a considerable amount of time in, allowing myself to be drawn to certain images for reasons that may be inexplicable to me at first. As I work further into a project, I may also write about an image I’ve seen while photographing. One of my chief obsessions as a bookmaker is exploring the relationship between text and images, and how the two can illuminate each other.

If I’m fortunate, some of these images slowly begin to show me what a project is truly about, a humbling process since the work guides the project, not the author.

How would you describe your own photography and how would you describe each other’s photography?

A.W.: I love the deep poetry and subtlety of Rebecca’s work. Her landscapes, still and meditative, also feel spontaneous. Unlike the monumentality of much landscape photography, her photographs feel intimate and unstudied—a pure and immediate poetic response to the world around her. Somehow, when looking at her photographs from “My Dakota,” or from her new project “Night Calls,” or from our collaborative projects, I sense a profound weight — the weight of life, death, love, time and memory. Rebecca has a unique ability to discover the metaphors that guide and permeate her work.

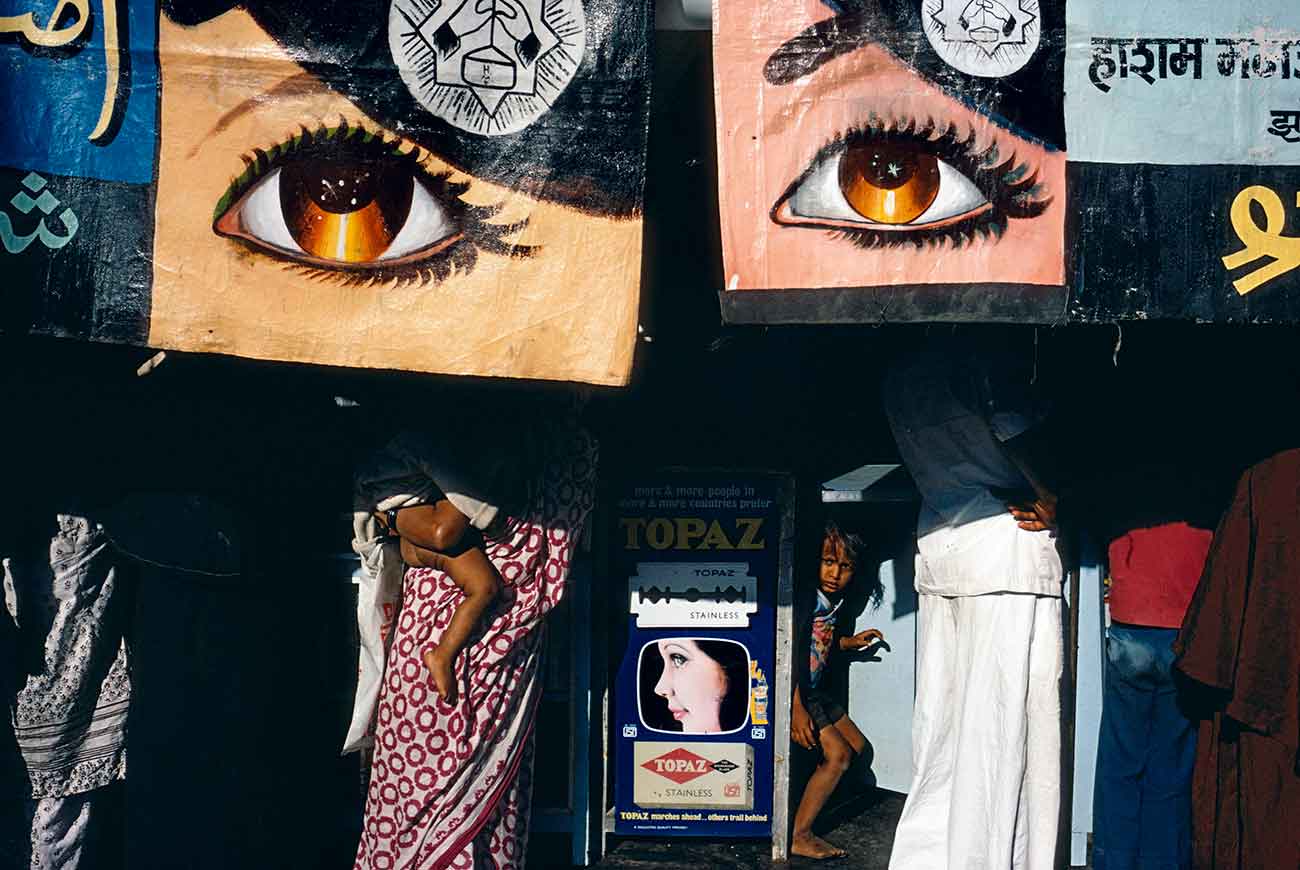

Whereas Rebecca’s work strikes notes of deep emotional complexity, I tend to be drawn toward visual complexity — the question of not just how “that” and “that” can coexist, but how “that” and “that” and “that” and “that” can inhabit the same frame. I’m often pushing the image toward the edge of chaos.

R.N.W.: I admire how Alex embraces the chaos of the world. I especially love the raw energy of his frames, which are often fueled by an array of visual paradoxes clashing and dancing with each other—hot light and deep shadows, vibrant reds and melancholy blues, beauty and suffering—all held before our eyes for one dynamic, sometimes surreal, sometimes gravity-defying moment. Looking at his energetic and complicated street photographs, it’s as if one can see something one can hear—the pulse of the street in all its startling, confounding, cacophonous glory.

I tend to be drawn to stillness and silence and reverie — and to those complicated emotional depths that can only be hinted at visually, those mysterious, subtle qualities that somehow quietly imbue or animate a landscape or still life or dreamy portrait of a person or creature.

How do you manage working together as well as living together?

A.W.: We respect each other’s work as well as the relationship — and try to find the right balance between the two. We find that it works best when we have at least three projects going on at the same time: two individual — one of Rebecca’s and one of mine — and one collaborative.

R.N.W.: Our individual projects give us the freedom to follow our own creative rhythms — also providing us with a healthy period of time away from each other, which, as long as it’s no more than three weeks, we’ve found rejuvenates our relationship. (I’ve always loved those lyrics from the Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks song “How Can I Miss You When You Won’t Go Away?”) Our collaborative projects are more complicated, but we often find their creative tensions push us to explore new photographic territory, causing us to question and sometimes to expand our visual vocabularies.

That said, I don’t think we could do this complicated dance if we didn’t have a sense of humor, a deep respect for each other’s work, and, most importantly, a love for each other that enriches and suffuses our lives as well as our work. Last year, as Alex and I struggled with the sequence for “Slant Rhymes,” we almost gave up on the book. Then it dawned on us that “Slant Rhymes” is a kind of unfinished, elliptical love poem, a metaphor for our long relationship. A few months later, we wrote the last paired text piece in the book:

“For some 30 years, we keep pouring words and images into the space between us, trying to fill it up.” —R.N.W.

“Is this our beautiful and impossible task?” —A.W.

Alex Webb has published 16 photography books, including The Suffering of Light, a survey book of 30 years of his color photographs. He’s exhibited at museums worldwide including the Whitney Museum of American Art, N.Y., the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A Magnum Photos member since 1979, his work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and other publications. He has received numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007. His most recent books are La Calle: Photographs from Mexico, Memory City (with Rebecca Norris Webb), and Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image. For some 20 years, the Webbs have taught photographic workshops together on six continents.

Originally a poet, Rebecca Norris Webb often interweaves her text and photographs in her six books, most notably with her monograph, My Dakota—an elegy for her brother who died unexpectedly—with a solo exhibition of the work at The Cleveland Museum of Art in 2015. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Cleveland Museum of Art, and George Eastman Museum, Rochester, N.Y. A new edition of Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (with Alex Webb) will be published in 2018.

”Photos need to talk, so words are not always needed. Slant Rhymes is a photographic conversation between two Rebecca and I, as we work together and apart.”

Source: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/08/29/a-marriage-of-lives-and-photos/#