Wong Kar-Wai’s Masterpiece ‘In the Mood for Love’

My tenuous geographical connection to Wong Kar-Wai‘s 2000 masterpiece is, ultimately, a bit immaterial. Unlike many contributors to this series, my favourite film doesn’t reflect something particular in my own life. On the contrary, In the Mood for Love’s glory is its universality. A seemingly slight plot – man and woman move into the same cramped apartment building, gradually realise their respective spouses are having an affair and develop their own halting romance – is the platform for profound and moving reflections on life’s fundamentals. It’s a film about, yes, love; but also betrayal, loss, missed opportunities, memory, the brutality of time’s passage, loneliness – the list goes on.

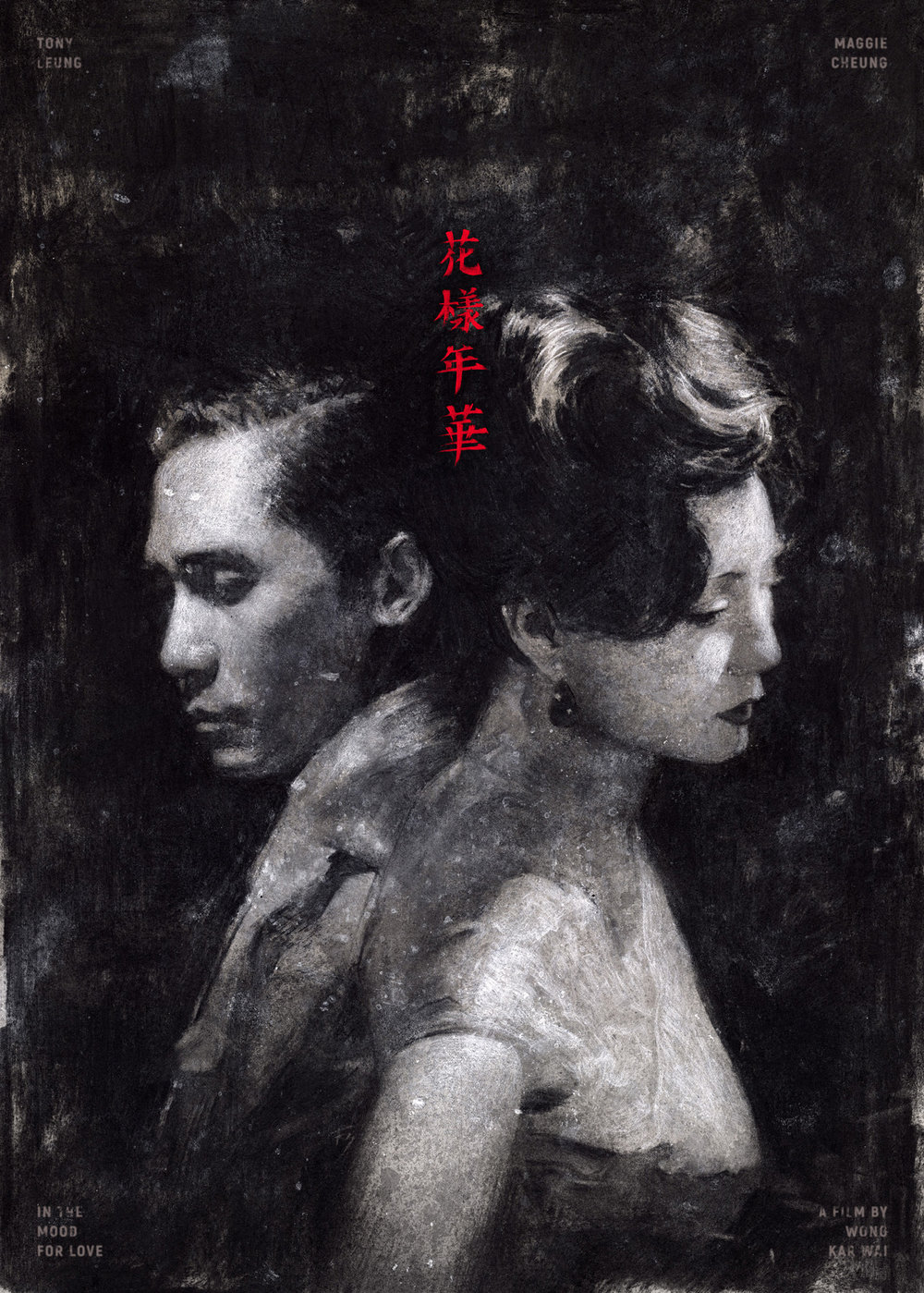

There are many reasons to adore the film, most obviously its almost unworldly, dream-like beauty. As a lead couple,Maggie Cheung (in a succession of figure-hugging cheongsam dresses), and Leung, with the slicked hair and hangdog face of a silent movie star, are among the most gorgeous in film history. Wong’s camera, guided by his regular cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, lingers lovingly on them for minutes at a time, saturating the screen with heat-muggy colours and light. For some critics the beauty seemed almost a distraction and – in a fate shared more recently by Tom Ford’s grossly under-rated A Single Man – many dismissed In the Mood for Love as little more than a bauble, an ultimately unfilfilling treat for the eyes.

I find this bizarre. I can’t think of a more moving, or more cleverly-told film, one which uses the whole lexicon of cinema so effectively. The camera lurks in doorways, down passageways, through windows, almost spying on Chow and Su Li-zhen (Cheung) as they seek solace with each other amid the paradoxical loneliness of a crowded city. Wong also uses music to brilliant effect, most obviously Yumeji’s Theme, the recurring, mournful cello refrain which follows the couple around the rainy streets. Never has popping out to get some noodles seemed more glamorous, or more sad. Elsewhere, Nat King Cole’s familiar tones become mysterious, almost mocking, as he croons “Quizas, quizas, quizas” (“Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps”) at them in Spanish.

Deliberately limited in scope, the plot, supposedly worked out over a year of part-improvised filming, is hugely clever, not least for what it leaves out. We never see the cheating spouses, just feel their impact. The few other characters – mahjong-mad landlady Mrs Suen, Chow’s buffoonish friend Ah Ping, and Su’s philandering boss, feel abrasively coarse against the lead pair’s quiet grace. Chow and Su’s relationship, in particular, is wonderfully ambiguous. Do they simply choose not to take the relationship further (“We will never be like them,” Su’s character says, bitterly, of their spouses), or are they both waiting for the other to act? For all the heartbreaking decisions and coincidences which, ultimately, keep them apart, could their romance even have thrived outside the counterpoint of their shared betrayal?

In lesser hands, the finale, where Chow whispers his unheard regrets and feelings into a stone hollow at Cambodia’s Angkor Wat temple complex, before sealing them inside with mud, could be absurd, melodramatic. Wong makes it heartbreaking.

In the Mood for Love is so good that it’s baffling how hapless Wong has seemed since. The half-follow-up, 2046, was similarly lustrous but terribly thin. Then came My Blueberry Nights, starring (God help us) Norah Jones, Natalie Portman and Jude Law. Here’s hoping his next film, bringing back Leung, is a return to form.

Peter Walker

————————————————————————————————————————————–

—-

The Study 1.

The Hong Kong Second Wave filmmaker loves synchronicity.

The films of Wong Kar-wai, specifically In the Mood for Love, are vivid portraits of desire (and often, the desire OF desire). In the Mood for Love specifically embodies this through a lyrical visual storytelling technique that creates a feeling of interfilm interaction between shots and components.

This is the theme of interaction that courses through the film, finding motif in visual and sonic elements to echo the plot details of the film itself.

Essayist Catherine Grant edited a video comprised of a synchronous compilation of images from In the Mood for Love’s ‘Yumeji’s Theme’ montage sequences to give viewers the sense, broken down, into what Kar-wai accomplished so subliminally.